A brief political history of liberalism, and the U.S. left and right

How did the U.S. get here?

*prenote: I am learning a lot as I write this, and also formulating my views as I write—I am not coming from a definite place trying to preach any one way here. Also this is very long. If you are reading it directly in your email, it might get cut off. Use the link to the blog.

“You are a liberal, I am a leftist, we are not on the same side.”

This is a comment I saw online recently, and am looking to evaluate, in a very roundabout way—and probably not just within this one entry. Certainly if you’ve spent time in online political spaces, or anywhere Democratic Party orientation or policy is discussed, you will have come across this seeming divide, with the groups blaming each other for election losses, legislative failures, and the inability to combat a rising tide of fascism in the US.

Beginnings of Liberalism

It’s important to first note that the way leftists use the word "liberal” and the way that mainline American Democrats (and Republicans) use the word “liberal” are not the same. Those identifying as leftists are generally using it in the most traditional, international sense, which gained popularity in the Enlightenment era of Europe (it’s philosophical founder is considered John Locke, if you want to go on another philosopher exploration)—an ideology that centered individual freedoms and rights, including right to private property, and right to have a say in their governance. Its opposition is restriction of freedoms, government control, authoritarianism, monarchy, enforced traditions, as well as enforced collectivism. You could actually say that the recent “No Kings” protests are based specifically on traditional liberalism.

This time from the later 1600s to the 1800s were when people in Europe were waking up to an idea that maybe their lives shouldn’t be lived at the whim of inconsistent tyrants and maybe their work should be going towards enriching themselves and their families, rather than kings and aristocrats. Thus people became interested in transitioning their governments away from absolute monarchy, and the economic systems away from the feudalism and mercantilism that saw the fruits of endeavors go to the monarchs and nobles, who then bestowed success on those of their choosing. The alternative ideas that caught on were generally republicanism (again, not present day American Republican—this is believing in republics as a form of government), and market capitalism, as espoused especially by Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations, who saw that mutually beneficial trade between different individual entities, and across nations, made both parties wealthier than those that considered their goods as protected regional or national assets and wanted to stockpile them or enrich themselves by charging a high price to let others have access to purchase them (tariffs/taxes).

New Governments, and the origins of left-right thinking

These aspects of liberalism formed the theory underpinning the new government of the United States, which was traditionally liberal through and through. Around the same time, it was inspiring the French Revolution, which is actually also where the identifications of left, right and center were first used in a political sense. The French never had a real national legislative body until the start of the Revolution, and when it formed, the defenders of the monarchy and the liberal revolutionaries sorted themselves to sit among the like-minded, and it turned out the royalists were sitting to the assembly president’s right and the revolutionaries to the president’s left. Thus the association of right with conservatism and traditional systems and left with progress and revolution (and also liberalism) was born.

This highlights an aspect, though, that what is left and what is right is entirely contextual on the predominant system in place, and what the status quo is. In 1789 France, the status quo was religious monarchy, so liberalism was very left of that. A traditional liberal was a leftist at this time. In 2024 United States, the status quo has been liberal democratic republic, so traditional liberalism is no longer left—it could be said to be center or center-right, with Trump’s fascist movement being far-right. This idea is very related to what we now call the Overton Window, designating what are considered the range of acceptable ideas in a society. I’m going to come back to this in the future, because I see it as a very central part to deciding what the right political actions to take are in our two-party US system in particular.

Limitations of Liberalism and a New Version: Social Liberalism

So, what grew into the left areas in this time? Well as liberalism became more implemented in governments and systems, observant people noticed that the benefits of these freedoms did not fall equally to people. An original liberal in the sense of John Locke, and society at the time, would have seen the freedoms of liberalism applying only to White men, as they were the class that was allowed access to politics. As time went by and more people gained access to education and the ability to disseminate their points of view more widely, more of the classes who were denied access were able to both organize toward seizing access to those freedoms, and also convince those in the privileged class(es) to sympathize and support their access.

Additionally, they noticed that the individualistic system of market capitalism favored those who originally began with ownership of land and capital (often the same as the old nobles, but also including wealthy traders) and that the realistic freedom of those who did not begin with those things was very limited, being essentially forced to sell their labor (consisting of most of their usable time) to gain access to food and shelter.

The combination of these groups that wanted to expand access to the freedoms of liberalism generally became known as social liberalism, and was to the left (less traditional power, expanded access, more distributed benefits and power through the population) of traditional liberalism. It’s also a bit of a departure from traditional liberalism in that it requires additional government action, and not pure individualism, to protect the expanded rights and access. Some collective will that is beyond just the individuals in question, who don’t have the power to enforce their will on their own, thus the will is exerted through the state, which by liberal principles, has the consent of the governed.

The list of influential social liberals is so long it’s hard to say who to highlight, but a couple I will point out who embodied a number of different facets: Mary Wollstonecraft, early feminist whose adventures in the French Revolution I will expand upon sometime soon, Fanny Wright, whose involvement in early utopian socialist experiments I also want to explore more, Frederick Douglass, the famous abolitionist who escaped slavery and whose support for women’s suffrage is a very early example of intersectionality.

Utilitarianism

I also want to highlight the English philosophers Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill (who Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy calls “the most influential English-speaking philosopher of the 19th century”) who championed various expansions of freedoms and were examples of social liberalism coming from privileged allies. Beyond their general stances though, they are particularly influential in their development of the consequentialist moral philosophy of utilitarianism, an important new (at the time) counter idea to Kant’s deontological rule-making we have discussed in prior entries. Utilitarianism is the idea that ethics should be fully defined by the actions that produce the greatest sum total welfare and happiness (the economic concept of utility—John Stuart Mill also wrote the primary textbook on economics that was used all throughout the latter 19th century) among all people.

Unlike other ethical structures of the past, which could always write off some other groups as unimportant, utilitarianism was necessarily progressive in some ways, in that it demanded the counting of all people in its moral calculus. It’s not without flaws, especially when trying to apply it as a sole governing rule. You could very easily come up with scenarios wherein tyranny to some minority benefited a great majority, as illustrated in the speculative fiction of Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” or Ursula LeGuin’s “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.” It also is one of what I call cold philosophies, that reduces all guidance on human behavior to some math calculation, which is lambasted in Dostoevsky’s brilliant Notes from Underground (more on this one later as well, it's perhaps my favorite novel of all time). Economics itself has been referred to as “the dismal science” though I find it not so off putting as a scientific approach to study of behavior, rather than a prescriptive guide for behavior which is meant to act on a much more human level.

The relationship between utilitarianism and imperialism is also fairly complicated (something we are going to see as a recurring theme with liberal and left ideologies here). John Stuart Mill himself was an employee of the East India Company starting from the young age of 17 and continuing for 35 more years until the Company was dissolved and the British government took control directly, which he declined to continue as an advisor to, disagreeing with the approach. He wrote arguing for a system of benevolent despotism toward those societies that he thought were not likely to respect or elevate their peoples in their traditional styles, while writing against the American “human cattle” style treatment of slaves and Native Americans; something some have labeled “tolerant imperialism”. The paper there seems interested in pretty ardently defending him while noting that he clearly does not see the Indian people as equals who are fully ready for government of their own full consent, a paternalistic view, but he did think that they should be equally calculated into utilitarianism’s total happiness equation and that it was England’s duty and burden to help elevate them. A view we might see as pretty distorted, but having been basically inserted into the fold of this imperialist force and enlisted in its communications bureaucracy at that young an age, making promotion of it a personal duty, it seems hardly surprising.

It's something that's an argument up to today, the question of the role of liberalism in the improvement of conditions of the world; that in a couple hundred years under a mostly liberal world order, world poverty has declined very significantly and continues to clearly decline. But whether that’s been worth the wholesale upending of cultures, commandeering of resources, multitudes of missteps, and success of bad and selfish actors, is definitely a question. As is whether that steep decline in poverty could have happened in other ways, or if ugliness is unavoidable.

The New Deal

Social liberalism rose to prominence at various points in the U.S., in the abolitionists, women’s suffrage movement and the Progressive Era, but it most prominently was defined by the New Deal and administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt, which expanded the role of government greatly, as the weaknesses of the hands-off approach to economic administration became apparent as a lack of standards allowed things like bank collapses causing the Great Depression. His government directly intervened in the economy, abandoning the hands-off approach of classical/neoclassical (it had already been broadly revised at this point) economics and following the new ideas of economist John Maynard Keynes, spending government money deliberately to circulate money to revive economic activity and help those who had been impoverished, while also putting into place programs to regulate activity and remedy pain points. It included agencies to directly employ the unemployed in infrastructure projects, the Works Progress Administration and Civilian Conservation Corps. Many more of the regulatory institution names will also be familiar.

1933 Banking Act: Created the FDIC to insure bank deposits, Glass-Steagall regulations preventing commercial banks from securities speculation. This part was repealed in 1999, and whether the deregulation actually led to the subsequent financial crises is a matter of debate, as it had already been chipped away at, and alternatives to engage in speculation established, so it was a bit archaic. But it’s clear no efforts to modernize regulation were really kept up-to-date in its place.

Creation of the SEC to regulate markets and protect individuals from large scale market manipulation by insiders. National Labor Relations Act for protection of unionization which established the NLRB. Fair Labor Standards Act, establishing 40 hour work week, national minimum wage, banning child labor. Social Security Act creating the Social Security system.

This approach was extraordinarily successful in remedying the ills that had been building in the U.S., and as such defined the American left for generations. This type of social liberalism became the American definition of “liberal”, and became directly associated with the Democratic Party, which was the new alignment created by the election of FDR as a Democrat in 1932. In a historical sense this would be termed modern American liberalism, and was in essence, a reaction to the failures of traditional liberalism. When someone in the U.S. identifies themselves as a liberal, it’s generally in this sense, and not the traditional liberal sense.

1960s: High Water Mark

It was further developed in the 1960s by the Great Society program during Lyndon Johnson’s administration, the Civil Rights Acts, Voting Rights Act (another one that has been essentially gutted by recent Supreme Court decisions, allowing restrictive laws that might influence different segments of the population’s access to voting to be freely enacted by states), creation of Medicare and Medicaid, and other initiatives. The civil rights initiatives alienated a large part of the remaining conservative wing of the Democratic Party, the southern white bloc which had been strongly Democrat since the Civil War (Republicans were the abolitionist party) that soon would switch en masse to the Republican Party. The modern American liberal became mostly co-terminal with the Democratic Party, and people who wanted to stick very strictly to the older traditional ideas of liberalism, with a more hands-off government regarding regulations on the economy, and systems that favored those originally in power, became the Republican Party and modern American conservative movement.

The Imperialism Trap: To intervene or not to intervene, that is the question

All this modern American social liberalism stuff seemed quite popular, no? So what happened? For one, the accompanying foreign policy was a lot more of a mess. It's complicated even for those being true to social liberal values. If one sees others elsewhere in the world being denied freedoms and self-determination and opportunity for prosperity, the ideology’s response is to intervene to try to help them. If, for example, the U.S. believed that communism as it was practiced in the world at that time was harmful and oppressed the freedoms of those it governed, it could see a duty in liberating them. However coming from a strong country, this is by nature imposing its views and values on the situation, inserting its interests and bringing it into its sphere of influence, which is generally what replaced direct colony holding as the primary means of projecting power, and very easily tips into imperialism. At the same time as it is possibly helping those in question (and the “helping” can be very, very dubious) it is also making it more favorable for commerce, which is really the strongest form of imperial power the U.S. wields.

Why can’t we change foreign policy very much?

So liberalism, which in principle stands in opposition to traditional imperialism, can still end up propagating it—something of a contradiction. Also, by nature there is just less ideological control of foreign policy allowed. Just because our president switches from Democrat to Republican, other countries don't revise their whole image of our country. If the UK and France were allies of ours, they are generally still going to be allies, and we are going to be partially party to a continuing agenda no matter what. There is an unavoidable continuity. So if prior administrations feared the spread of communism and formed alliances to prevent this, promising to defend certain governments or factions, it’s not necessarily feasible or ethical to abruptly renege. I am not claiming that the above motivations are exactly what individually motivated any people in their foreign policy actions, but that it is a way in which someone who was ideologically consistent could very well act.

This is also why we as voters feel a lot more powerless regarding voting on foreign policy, as I’m sure people have experienced recently with regards to the Gaza crisis. We rarely get to actually vote on completely opposing platforms of foreign policy; it’s just the nature of government, and I’m not convinced there will ever be a remedy to this no matter what governmental system is in place. It will always be the case of not being sovereign and unilaterally being able to impose (or if deciding to do so, it’s extremely hazardous) like we can domestically, but being part of a web of interconnected interests and alliances. So we have to find the small differences that matter and push for realistic course changes.

Socialism is not immune

I actually see this challenging contradiction in any system that purports to care about others. For example, the USSR (I’m going to do a lot more detailed posts on socialism/communism coming up, but just mention it a little here), which defined itself as internationalist, rather than nationalist, and anti-imperialist, saw as its duty to support the freedom of the proletariat from liberal systems which in its view, were oppressing them wherever that happened in the world. Many countries were in its sphere of influence that it had “encouraged” to adopt its system of government. At times populations of these countries would try to infuse more liberal principles into their governments and rise up against Soviet influence, and the USSR would use their overwhelming military to suppress the uprisings (or in their view protect the proletariat from growing capitalist influences and maintain the strength of the global communist whole). See Hungary 1956, Czechoslovakia 1968, East Germany 1953. Illustrating the contradiction, the Hungarian Revolution would fracture communist parties in the West, as party establishments generally followed the Soviet script, while members often saw it as suppression of the will of the population there and not acting in their best interests.

The Worldwide Trolley

The only ideologies that seem to escape this contradiction are the ones that are unapologetically imperialist, that see assimilation of peoples as the goal, like the Roman Empire, or nationalist expansion as the goal, like Nazi Germany. If the social liberal or socialist/communist governments decided instead to remain non-interventionist, this seems to create something of a massive scale trolley problem. There have been a great many instances of genocide and ethnic cleansing, for example, in modern history. I think most would agree that it is a duty to not lend support to genocidal forces, however the question of whether our country has a duty to intervene to try to stop it, is much trickier, because intervening pretty necessarily entails imposing some degree of suffering and likely death, on innocents, as well as imposing your idea of order. The US/NATO, for example, has chosen intervention in some instances: Serbia in the 1990s, and not in others: Rwanda in the 1990s (Bill Clinton noted that this was a major regret, and was informed by consciousness of the hazards of intervention presented by Somalia just a year or two earlier).

Supposing for instance that it could be realistic, like if the US were not in an established set of alliances with Israel and other countries, and instead Israel were a neutral country to us, would you propose a US military intervention via bombing or invasion to stop what seems to be a genocidal campaign against Palestinians by them there? Or impose harsh economic sanctions causing starvation and suffering if their rogue government doesn't bend? Or would you say it's unfortunate but not really something in our power to stop? It's an open question, I don't really know what the right answer is.

Vietnam, the New Left, and the Reckoning of 1968

What I’m getting at with all of this, is that we end up with miscalculations like supporting coups that entangle the country and progress to disastrous wars. Because socialism, which made up the most left side of the political spectrum for most of its existence, never really was able or allowed to take off in the U.S. compared to elsewhere, the Vietnam era really introduced a major challenge to the modern American liberal from the left, termed the New Left, for the first significant time, with the strong anti-war movement, democratic socialist sentiments (which had split from Soviet-inspired socialism over the 1956 Hungarian Revolution), and more militant racial equality groups like the Black Panthers. This came to a head in 1968 when two popular anti-war candidates, Eugene McCarthy and Robert F. Kennedy, challenged Lyndon Johnson (who had won his 1964 election with the highest popular vote portion in American history) for the Democratic presidential nomination. So badly did Vietnam wear on him that Johnson actually dropped out, with his VP Hubert Humphrey taking his place and generally maintaining his course on continuation in the war (it seems he tried at points to break away from Johnson’s orbit, but Johnson generally held him in contempt and bullied him into line).

McCarthy and Kennedy mainly competed in the primaries, while Humphrey stayed out of them, relying on winning delegate support directly, rather than via the public (the majority of states didn’t have primaries at this time with more closed caucuses). Kennedy ended up being assassinated by a Palestinian immigrant over his support for Israel in the 1967 Six Day War, and a consequence of this was the delegates he had won became uncommitted, and also generally moved to Humphrey’s side. So the Democratic National Convention (highly recommend this article) came in Chicago, with a large contingent of anti-war protesters assembling. Amid fights inside the convention, Humphrey won the majority of the delegates and became the nominee despite not competing in any primaries, while outside the convention, the Chicago police under mayor Richard Daley, who was determined to demonstrate the law and order there, brutally attacked the protesters in a police riot.

This ended up devastating the entire spectrum of the Democrats and the New Left, as Humphrey went on to lose the election to Richard Nixon who presented the concept of the “silent majority” who were tired of all this commotion (I see the silent majority concept as possibly having come into play in 2024). Contributing was the fact that the the long-time Democrat White deep south abandoned the Democratic party over the Civil Rights Acts, and in this election went to the White supremacist third-party candidate George Wallace, while in the future joining Republicans. And Republicans went on to control the White House for all but four years from 1969 through 1992. The fallout from the 1968 disaster is actually why the Democrats revamped their primary system and now most delegates are awarded through state voting which happens in all states, though some were kept as superdelegates.

A Man of the Times

I was always especially struck by this in the person of Phil Ochs, who was a New Left singer-songwriter who wrote many political/protest songs, including the very topical to this post Love Me, I’m a Liberal, a satirical skewering of the typical American liberal. We had an amazing album of a live concert of his in Vancouver 1969 where he talked about Chicago-induced sadness—in the intro he did to the song “William Butler Yeats Visits Lincoln Park and Escapes Unscathed” he dolefully says “More than anything else, Chicago was probably sadder…it was exhilarating at the time, then very sad afterward because something extraordinary died that day, which was America” speaking to the crushing of the idea that America could ever be what it promised, rather than what it always seemed to actually represent.

It’s a beautiful live recording, and I also count the song The Crucifixion as one of those tour de forces that are the pinnacle of expression, in the same vein as Kendrick Lamar’s Sing About Me, I’m Dying of Thirst that I mentioned last time. A lot of these songs were on Ochs’ 1969 studio album Rehearsals for Retirement which featured the cover:

He ended up spiraling into depression and alcoholism from here, and left recording in 1970, dying by suicide in 1976.

Neoliberalism and Neoconservatism (why do they have to name these in such a confusing way?)

Anyway, the time from 1968 to 1992 where Republicans controlled the White House for all but four years: It became an era of undoing what had been social liberal policies, regulations and tax structure with the advent of Reaganomics calling back to the old traditional liberal values of absolute freedom of markets and favoring of those with established power and success—this revival has been termed neoliberalism (although it’s primarily only used by critics, it was rare for anyone to call themselves it), which was a reaction to the mid-century dominance of social liberalism. Following 1968, and the Vietnam War, there was also a trend of the Democratic Party moving away from support for large-scale foreign interventions, following what seemed to be the popular anti-war sentiments of its base that had been revealed. This caused a breaking away of the very interventionist and war-tolerant or warhawk wing of the Democratic Party to the Republican side, and these became known as neoconservatives. This influence became very prominent in the Republican Party, eventually culminating in the rise of figures like George W. Bush, Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld, and the long-term nation-building wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

I see the terms neoliberal and neocon thrown around, often seemingly interchangably and with little discernment, nowadays. The main thing to remember to identify them is neoliberalism is primarily an economic ideology, concerned with free-market economics, low taxes, little government involvment or regulations, and neoconservatism is primarily a foreign policy ideology, concerned with interventionism. They both primarily grew and have been mainly promoted within the Republican party (neocons after their early versions left the Democrats).

They have also become very popular identifiers thrown at figures like Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton (Secretary of State under Obama), Joe Biden, etc. as criticism from the left, which I’m not convinced are very accurate. In terms of foreign policy intervention, they have done some, but none even remotely close to the encompassing nature of Vietnam, Afghanistan or Iraq, with the latter two being inherited situations. Biden oversaw the withdrawal both from Afghanistan and Iraq, and if you look at the Obama administration’s handling of the massive crisis in Syria, it’s a huge departure from neocon thought. The domestic economic policies they espoused have largely been from the social liberal playbook, with Keynesian spending to recover from the largest economic downturn since the Great Depression, government propping up companies (which may be harmful, but is the antithesis of liberal), and Obama spending an unprecedented amount of political capital and time pushing healthcare reform that added a ton of government input and required a number of new taxes to pay for. Joe Biden also worked harder for labor movements than any president in recent memory.

The seeming inaction and stagnation of policy I think is where people seem to get the idea that these are neoliberal figures, but that is not really a matter of their policies but the political situation the country is in because…

Obstruction, and the Man Who Broke Politics

However it wasn’t just the fact that there was this period of rise of neoliberalism and neoconservatism that got us to where we are today; after all, policies were always able to be changed, new legislation written. But no, because at this point during their rise in the era of Reagan enters the man who killed US politics (I used to be able to access this article for free, I don’t know if others can, but now I can’t anymore. But here is an NPR interview about it). I’m talking about long-time congressman Newt Gingrich, and I REALLY REALLY recommend either reading the article or listening to the interview because the writer McKay Coppins states it better than I could, and I think it explains the state of American politics now more than anything I’ve ever seen.

He is quite an influential figure. And I think that a lot of people forget about him, but I don't think we should for many reasons.

GROSS: What are the reasons?

COPPINS: Well, for one thing, he's influential in this current Trump administration. But also, his career is important to understand if you want to understand how we got to this point in our politics. He entered Congress in the '70s. And if you kind of trace the last 40 years of his career, you'll really come to understand how our politics has devolved into this kind of zero-sum culture war. You'll see the way that he pioneered a lot of the tactics of partisan warfare that we now take for granted as just a common fixture of our political landscape but were actually important innovations by Newt Gingrich and his allies.

And more than anything, I think that if you look at the way that he gained power in the first place, he did it very deliberately and methodically by undermining the institution of Congress itself from within by kind of blowing up the bipartisan coalitions that had existed for a long time in Washington and then using the kind of populist anger at the gridlock in Congress to then take power. And that's a strategy we've seen replicated again and again all the way up into 2016 when Trump was campaigning on draining the swamp. This is a strategy that may seem kind of commonplace now but that Newt Gingrich was one of the premier architects of.

Stuck in the mud with Newt

The Atlantic article talks about how he loved and took inspiration from the animal kingdom, bringing the values of survival of the fittest, kill or be killed, do whatever is needed to come out on top to politics, seeing moderate Republicans and those who compromised with Democrats as weak and too nice—it’s all about the strategy of winning rather than any sense of governing. He ushered in a new wave of young Republicans in his image ready to do political battle and drive wedges between any cross-coalition partnering, which has destroyed the legislature’s ability to actually legislate. This causes people to hate the government and think of it as useless, so they can point to this to support their agenda of dismantling the government structures that defined social liberalism. It takes advantage of the fact that it’s easier to destroy and then point to ineffectiveness, than it is to build and then point to effectiveness.

Because the Republican party has fully adopted Gingrich-ian tactics, and he was succeeded by a perfect protégé in Mitch McConnell who is known for his gridlocking and obstruction throughout the Obama presidency, it has essentially cemented legislative philosophy where it was when Gingrich entered the scene, which was at that stage of Reagan’s neoliberalism, even when Democrats with a more socially liberal philosophy have won office and majorities (which are far from impervious to obstructionism).

The science of cooperation: We go to prison with Republicans

The study of strategy in a scenario of combined cooperation and competition, such as politics, is a branch of economics called game theory, and the situation in our two-party legislature is very similar to the most classic game theory example, called the prisoner’s dilemma, if you make the two options (a) cooperate and (b) single-party only with obstruction. It turns out extending the prisoner’s dilemma to repeated situations actually gives a scientific explanation as to the very evolution of the concept of cooperation: cells cooperating to form more complex organisms, humans cooperating in society.

But why has it broken down here though? Two reasons: one, Republicans have decided they were, and Democrats still are, pursuing too “nice” of a strategy without enough retribution, which can be exploited. And second, the payouts aren’t actually equal between the two parties. The 1,1 scenario in the video that corresponds to no cooperation from either side, or gridlock, is more like 1,2 or 0,2 in Republican favor because of their ideology of wanting the government to do less (note that these number scorings use “utils” and the exact concept of economic utility I discussed in the utilitarianism section). Even the things that a social liberal doesn’t particularly want, like overspending in military or mass incarceration, they see a moral quandary in just taking money and support away—making prisons suck more or making the military do a worse job has bad human consequences on the way to the desired outcome of lower support for imprisonment and military expenditure.

It’s actually a terrible strategy, the US just sucks

I want to also point out that the undemocratic electoral college system greatly skews our view of the success of modern American liberalism, and the contemporary Gingrich-style Republican party. If we had a national popular vote for president, everything about contemporary Republican politics would be seen as a miserable failure. It is not popular. Not a single one of the Republican presidents would have won the presidency without the electoral college system and its magnification of rural resentment since George H.W. Bush in 1988, 37 years ago! Republicans have won exactly two popular votes in the entire time since then, Bush in 2004 and Trump in 2024. However both of them built off of first terms where they would not have won; Gore would have beaten Bush in 2000 and he never would have had the big post-9/11 incumbency advantage, and Clinton would have beaten Trump in 2016 and no swing of the Republican party to his ideology would have happened. The fact that structurally the Democratic party has to fight an uphill battle every presidential election is a huge factor: a person in Wyoming’s vote counts almost 4x more than a person in California’s on an electoral vote-per-person basis.

Really a lot of the pain points of the present day could be a lot better if the constitution had just a little more foresight and were a bit better. For example, in the present day, it is essentially impossible that we will ever see a constitutional amendment—in a polarized setting, the agreement requirements are just too high (2/3 of House and Senate or 2/3 of state legistatures to get it to a vote, then ratification by 3/4 of states). The lifetime appointments of supreme court justices are clearly problematic. When push comes to shove, there is an implicit requirement of congress acting in good faith for any of the checks on the executive to actually hold up (otherwise as we’ve seen, impeachment is a meaningless and worthless process). For someone who was as adamantly against political parties as George Washington, the system he helped set up with its winner-take-all elections sure encourages there to be two dominant ones. It’s hard to blame them for not getting it perfect, though—there weren’t many prior constitutions expressly establishing republics in history to model it on, and there was no real way to know how big and all-encompassing the United States would grow to. The American Experiment is a pretty accurate term, and it may have finally reached the failing point.

Populist Fascism Comes to America

So anyway, by now we get to the Trump era, whose populism plays exactly on the intentionally inflicted inability of the government to accomplish anything. All the old rules must be tossed, let’s get some radical new perspectives on how to fix things. What Trump has done in his takeover of the Republican party is move it away from what was their standard neoliberalism, to something further to the right, with much more government involvement in enforcing traditionalist and nationalist views. In the old days this would have been monarchism and feudalism, but in the 20th century the ideology of fascism mostly took its place. It’s not necessarily too different from those old ideas, just a modern spin on them that takes advantage of nationalism (a trend that became popular after the days of kings ended) to gain the belief and buy-in of the common people, which didn’t necessarily exist in the old days—it didn’t matter if the peasants really believed in the king or not, they just had to do what they had to do and didn’t really have power. But more recently, populations have power, they read, organize, vote, and if necessary, begin a revolution. So fascism needs buy-in.

It was defined and established by Benito Mussolini, who was originally a socialist, but grew frustrated at the lack of ability class struggle and an international worker coalition was having to actually get anything done. He decided that for Italy to actually progress, it needed something that had more access to power, and that the classes had to come together instead and unite around their power together—still maintaining the collectivist spirit, but the collective was the whole nation of Italians, empowering the state to act definitively in the national interest, guiding the economy based on national needs, where anything that got in the way of this unity of purpose had to go. To this purpose there was an authoritarian executive, heavy censorship and suppression of opposing parties. Later additions to the ideology like Nazism would reinforce this sense of unity with the idea of racial purity and the out-group scapegoat, which weren’t huge parts of Mussolini’s classical fascism.

Trump’s movement, and his discourse, fits very closely with the fascist model, to the point I have no hesitation in calling it a fascist movement. Even the economic policy, global tariffs to enforce the national interest of having stronger domestic manufacturing and the desire to reassign American workers to the manufacturing sector to promote the nation is right out of Mussolini’s fascist economics, and flies in the face of neoliberalism’s free trade. There is still a strong base of neoliberalism that’s been in place, and I don’t think Trump would lean fully into fascist economics—by the height of WWII, Italy’s economy was something like 75% state owned, higher than anywhere other than the USSR. But he is creating a fusion that is heavily fascist on top of the existing base.

This party ain’t what it used to be

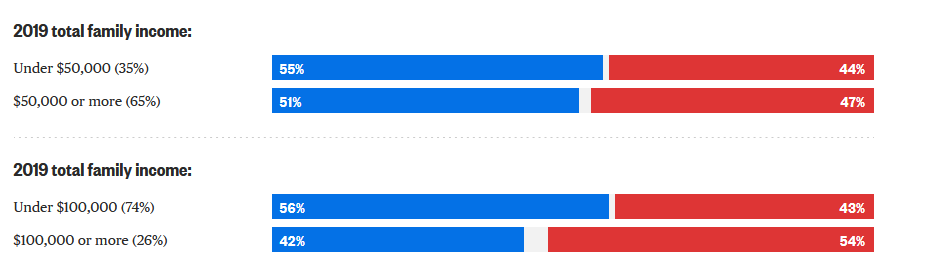

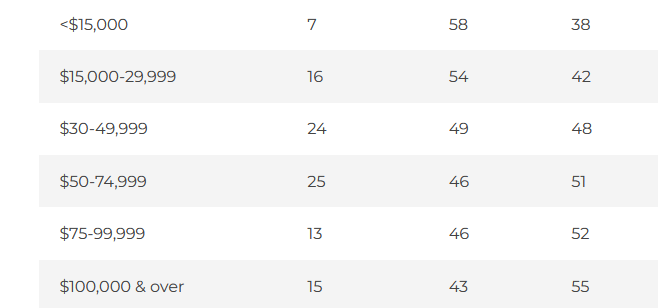

So what happens when Trump takes over and re-imagines the Republican party? It forces a re-alignment, where traditional conservative Republicans have to either move with him toward the fascist end of the spectrum, or jump ship because of their liberal baseline. Most went with him, but some (see Liz Cheney, and the Project Lincoln crew) broke away. But on the other hand, Trump attracted working class members and labor union groups who had traditionally been on the Democratic side, which tracks with the idea of him taking advantage of the “stuck in neoliberalism” sense people have. Looking at exit polls, the 2024 presidential election was the first time I’ve ever seen Democrats lean toward higher income and Republicans lean toward lower income.

2024 Election:

2020 Election:

2000 Election:

The current spectrum

So what does the political spectrum look like now? (I’m going to keep this to a relatively simple left-right line, though it really has more dimensions than that. The way people cluster, though, the approximation covers most cases.) It seems you have a big cluster of people on the right in Trump’s neoliberal-fascist fusion land (some favoring the former but OK bending to fascist policies, and some fully favoring the latter). This is the full Republican Party extent. Then you have a center portion of neoliberals who won’t tolerate fascism, and center-left of social liberals. The left would be the remnants of the New Left we talked about, which is no longer new, and the growing, mostly younger, proponents of socialism, which has seen something of a resurgence, especially compared to its historical popularity in the US. I believe the “stuck in neoliberalism and looking for a remedy” sense has caused a lot of this, and also the fact that young Americans grow up talking and sharing views online on international websites now, like Twitter and Reddit and such, so they are exposed to more international views and less likely to follow traditionally anti-communist US orthodoxy.

The Democrats have been trying to make a coalition of everything from the center portion of Republican deserters all the way to the new socialist leftists, but this is a frayed alliance due to the great variance of views contained within. Neoliberalism and socialism are at odds in most of their beliefs; Democrats are trying to corral all of them onto one side, however historically these two systems are not allies—socialism grew originally as a reaction against traditional liberalism. Fascism and neoliberalism are also at odds ideologically, but I’m not convinced the adopters care so much about being true to their principles.

Are these the liberals you are looking for?

Now as to the modern American social liberals who believed in Franklin Roosevelt and the domestic policies of Lyndon Johnson, there is some overlap with socialist thinking, and some overlap with traditional liberal thinking. For leftists saying these are “liberals” and opposing themselves to them—I can see why, since they generally still support similar institutions, but with more controls, as the traditional or neoliberals, and the term “liberal” is right there and not everyone is studying the distinctions in the different evolutions of liberalism. However I’d say it’s accurate to say they favor a mixed economy and are not opposed to public ownership in sectors like utilities, healthcare, large portions of land, and more, and strong governmental controls to address inequality, which are not opposed to more left views and socialism, and especially not my reading of classical Marxism (pre-Lenin), which I’ll discuss coming up.

Also, I think it’s just strategically ill-advised. Trying to put all social liberals with the neoliberals is just giving them a big and powerful coalition, while making the leftist sphere smaller and weaker. Candidates are less likely to try to appeal to a politically smaller and weaker group (or if they do, they don’t win), and it’s more beneficial then for them to appeal to the group that is now associating together, the full social liberal and neoliberal umbrella. Instead if social liberals and left-socialists emphasize their commonalities and show broad togetherness against the neoliberal style of deregulated economy, that’s now the popular platform for a candidate. I just don’t see the dismissing of the modern American social liberal as “liberal,” therefore against, as being beneficial at all.

As to whether we can actually get out of this mess that is present-day America, and What Is to Be Done (the Chernyshevsky version, the Lenin version, and the Matt version) I will need to talk about that in Part 2, because this is way too long already. A lot of this has been focused on more mainstream philosophies, so I want to talk about some of the more revolutionary ones. Let me know what you think, if it’s a good explanation, or you think I’ve gotten things wrong!

Leapfrogging past most of the substantive stuff to opine about left vs liberal... regardless of its origins, my whole life the vernacular of "liberal" meant leftwing and the opposite of conservative, and likewise "conservative" meant the reverse. Is it useful to describe political thought as two binary poles? Who cares, that's how probably 98% of this country understands it, and as far as I'm concerned, self-labeled "leftists" are the only part of the entire leftwing coalition in this country who feel the need to distinguish themselves from other leftwing people because they disdain them. Whatever people call themselves - progressive, liberal, leftist, Democratic - I don't care, so long as the label isn't used to factionalize rather clarify particular nuances of your own stances. But in practice that is almost solely what it is used for when self-applied, and then when Normies use the term to describe others they see zero distinction anyway.

It drives me absolutely crazy that "liberal" is often defined by people who specifically consider themselves not liberals. Conservatives of course use liberal as a perjorative, and I don't know why leftwing people think it makes sense to adopt that very same messaging. It's like, dude, to the people who you are trying persuade to vote for you and adopt your policies, *you are a goddamn liberal to them!* But even beyond that, so many leftists seem to view "liberals" as like, a crappier spineless version of all their own beliefs rather than a coherent ideology that might sincerely and intelligently disagree with particular positions or values, and so much of that comes from never actually respecting the people they consider liberals enough to listen to what they say they believe. One of the purest distillations I've seen of this was on ContraPoints' latest tangent about Daddy Politics:

"I'm also #concerned by the end of this video. While I've known I'm probably a bit farther left than Natalie, nothing about her videos has ever suggested she's a liberal, or wanted to create more liberals (in the American sense). Liberals are for Israel, genocide in Gaza, for profit healthcare, foreign wars, billionaires, stagnant wages, p. much stagnant everything. The status quo."

Natalie, of course, has talked all the time about what her actual views are and why she is satisfied with the label "liberal*," but this guy is like, "uhh, instead of actually listening to what you say, I'm just going to be confused that your label contradicts all the things that I accuse the label of believing." I very easily understand why leftists hate liberals so much, because I promise you on a personal level, I hate those people so much more than they hate me lol. Like the only people who have ever been truly nasty to me on the internet have been liberal-hating "leftists." And I still vote for their candidates, which is how we ended up with fucking Fetterman, something that I have yet to see any leftist try to reflect on what happened there. As much as it sucks that so many people are low-information Vibes voters or whatever, I think it's worth recognizing the reality that human interpersonal interaction is a very complicated, sophisticated thing that evolved over millenia. So much underpinning the notion of "trust" is going to be determined by interpersonal interactions and how people carry themselves generally, and that's vitally important for getting people on board with political projects. It doesn't matter how "objectively" good your platform might be, people need to trust that you'll implement it well, they need to trust that you aren't going to betray them or screw them over somehow, and a lot of the signals about that are sent just in how you behave as a person.

Anyway, her video about Daddy Politics was pretty good (small audience will see this link so I feel ok sharing it even though it is a Patreon bonus one https://youtu.be/x56kAvehyzk?si=Ac_qcUEF1A0kRzHl) and I think her observations about "leftism" vs liberalism are astute, albeit not the full explanation (nothing ever is.) Essentially that the rise of this particular incarnation of an American leftwing faction is in response to the social coding of Democrats as Mommy and Republicans as Daddy, and Trump's massive success as embracing that psychosexual Daddy affect and humiliating the Mommies in a way that transcends traditional conservative positions and values. There's a desire to harness that same power, I mean the "dirtbag left" in particular seemed to basically be saying it back when they were a thing people weren't ashamed to call themselves. We'll have a cross-party coalition of people who say the R-word, I guess, lol. A lot of online leftism I discard out of hand because in the end I don't really believe it is motivated by leftist values - they might be leftist positions, for now - but I don't understand how a person can truly believe in an ideology premised on an expanded social contract and also behave like a contemptible douche. In the meantime, I am likewise happy to embrace the feminine drudgery of the "liberal" label, where someone has to keep the day-to-day running while we aspire for a better world.

*Side note - people seem to be endlessly disappointed to learn that ContraPoints does not identify as a leftist and fequently says she is not one despite being smart and funny and having good ideas about things, and never once reflect on the possibility that this could be because she has a point about not being a "leftist." Another dimension to this is something another transfemme woman I follow on bsky laments a lot, which is that there is a contingent of the trans community (and some of the broader LGBTQ community too) that views simply being trans as a Radical Act, and as a result you are expected to be a Radical about everything else. It's an example she uses for how some lefist affect and positions are actually deeply anti-humanist and not really leftwing, because to forever be a Radical Act is to forever be an outside, oppressed minority and any attempts to rectify that would undermine the radicalism. And it actually is premised on the conservative beliefs about rigid social and gender roles, if being trans has to be more than just being a Person (who is trans.)

Lmaoo https://imgur.com/a/V7rFqzr